Larry McMurtry, in the preface to an early novel, writes this: "The knottiest aesthetic problem I fumbled with in Moving On is whether its heroine, Patsy Carpenter, cries too much." Do your characters cry? In public or private? Frequently? Never? If they don’t cry, what would make them cry? Know your characters! Let me tell you about Richie.

It’s Saturday and my friend Richie from up the street has dropped in to watch the game with me. As usual he’s brought a small cooler with bottles of Bud for him and Corona for me. I slide a frozen pepperoni pizza into the oven and cut up a lime for the Coronas.

Richie claims the recliner while I’m in the kitchen, so I settle in on the sofa. Richie tosses me a Corona and says "Think fast." I fumble but finally catch the bottle with two hands. Richie gives the out sign, like an umpire. "Almost an error there, Dave," he says. Then he pitches the bottle opener to me, the one he’s had since college, the much-travelled one with the well endowed metallic babe for a handle. I open the Corona and squeeze a lime wedge into the neck while Richie snickers and takes a big gulp from his Bud. He always snickers, but it’s never stopped me from adding the lime.

It’s my place so I control the remote. The game’s not on yet and I’m flipping fast and then there are cowboys on the screen so Richie says "whoa" and these two cowboys ride toward each other, and they hug and kiss, except that one is a cowgirl so it’s not Brokeback Mountain and Richie can relax. Then we hear a woman’s emotional voiceover saying, "The moment his lips touched mine I knew that we would never again be apart."

Richie calls out "Chick flick! Change it!" but I don’t, not yet. Then we see Kathleen Turner typing and crying, and she’s saying, "I knew then that we would spend the rest of our life together forever. Forever." And Kathleen Turner’s crying her eyes out and Richie’s groaning and covering his eyes and pleading "No more, no more, no more," and Turner says, through the tears, "Oh God, that’s good," and she types "THE END" and Richie is reaching over to grab the remote away from me but I stick it down my jeans and I know he’s not going in there.

Richie retreats to the recliner, folds his arms, and stares at me as if I’ve lost my mind. "Chick flick, man," he says, "chick flick," I tell him not really, that there’s lots of action and bad guys and jungle scenes, just wait for it. He asks me what’s the name of the movie and I tell him Romancing the Stone, and he says that proves it, right there in the first word. If it were Throwing the Stone, or Playing Football With the Stone, or Die Hard With the Stone, I think he’d give it a chance.

"Oh my God," Richie says, "she’s celebrating with her cat now!" It’s true, Kathleen Turner is opening a can of tuna for the cat and lighting candles to celebrate finishing the novel. "Make her stop crying," Richie says. "Please. Or just change the channel. Let’s watch Sportscenter."

"Is it the crying?" I say. "You don’t like watching women cry?"

"Well jeez, it’s never good when they cry. You know that. It means we’re going to end up losing."

"Okay," I say, "but what if the woman’s crying with joy because you’ve just given her incredible physical pleasure?"

Richie stops and thinks. He’s replaying the greatest hits from his love life. "Nope," he finally says, "never happened to me."

"Me neither." We’re so honest with each other. "Say, Richie, have you ever cried?"

"Nah, real guys don’t cry. Except maybe that one time I was a kid and I broke my arm and it hurt like hell. Have you?"

"A few times, I guess. My high school sweetheart ran off with a sailor. I told you about that one."

"Yeah," Richie says, "that’s why you always root for Army to crush Navy. Come on now, enough’s enough. Turn on ESPN."

I punch in the numbers and Kathleen Turner disappears and the Sportscenter guys come on. They’re dressed up in suits and ties, but I wish they’d just wear regular guy clothes like Richie and me and not sit behind a desk.

"You know what I hate?" Richie says. It’s a long list, the things Richie hates, longer than my list, although there are things that are on both our lists. "I hate it when some great ballplayer hangs ‘em up and rides into the sunset, but first he has to have the stupid press conference to announce his retirement and he starts bawling like a baby. Real guys don’t cry."

"I hate that too," I chime in. "Tom Hanks was right. There’s no crying in baseball."

"Yeah," Richie says, "if it was me, I’d just open a cold Bud and wave goodbye and say it’s been fun but I’m outta here and I’ll see you in Cooperstown." Richie in the Hall of Fame? That’s what you call your hypothetical right there.

Just then the front door opens and it’s my wife, Nikki, back from her workout at the gym. Richie grabs a Bud out of the cooler and shakes it up real good, then tosses it to her, along with the bottle opener, and says "Think fast," and she catches the bottle with one hand and the opener with the other. She played a mean shortstop in college. Then Nikki stands over Richie, who is fully reclined and fully vulnerable, and holds the Bud bottle kind of horizontal and tells him "Think fast" and opens it and watches it spurt onto Richie’s Bud belly, soaking his shirt, and Richie doesn’t get upset, he just laughs like it’s the funniest thing that ever happened and he looks at me as if to tell me, once again, that I married the coolest woman in the world.

Richie told me once that it’s great she works out "like us." I’m not sure what he was referring to by "like us," unless he meant the times we take a football out to the back yard and try to throw it and catch it without spilling our beers. Or maybe the whiffleball games in the back yard, which works out better because it’s easier to catch without spilling the suds, and you can swing a whiffle bat with one hand no problem.

Nikki plops down next to me on the couch and says, "Hey Dave, look, there’s your hero on Sportscenter, Peyton Manning."

"Best quarterback in the world," I say, and Richie starts in on his same old "Joe Montana, in his prime, best quarterback in the universe," and we turn to Nikki to settle the argument, and I know she’s always saying that Tom Brady is way cuter than Peyton, but she’s also loyal to me, so I wait for her to jump on the Peyton train, but instead she rolls her eyes and says, "You guys are pathetic. Best quarterback ever? No contest. It’s John Elway."

Then suddenly Nikki says, "Hush, it’s My Wish on Sportscenter." She grabs the remote so we can’t change it. My Wish is a long feature where they find this sick kid and tell their sad story and then they let them meet their sports hero and everybody feels warm and fuzzy. Don’t get me wrong, ESPN does it well, and you can’t say anything bad about being nice to sick kids, but Richie and I would rather be watching a game.

This week the My Wish folks at ESPN are telling the story of Dani, a 10-year-old girl who almost died from a brain tumor and now is having a little trouble walking. They show Dani watching a Michelle Kwan skating video at home when the phone rings and it’s Michelle and she talks with Dani, and Dani’s face, which was so damn cute already, just lights up. Then Dani and her family ride in a limo to meet Michelle at the rink, and Michelle hugs her and gives her the actual jacket that she wore in the 2002 Winter Olympics. Then she takes Dani on the ice for a skating lesson, and it’s the sweetest thing you ever saw.

I hear these muffled sounds and look over at Richie, who has a daughter the same age as Dani, and Richie is rubbing his eyes and trying to hide the fact that he’s shedding big tears. I nudge Nikki, who’s wiping away some tears of her own, and we both stare at Richie, who doesn’t dare look at us.

On the screen Michelle Kwan makes hot chocolate for Dani and gives her a big candy bar and talks to her softly, and then I can’t hold it any longer. Nikki smiles at me and touches the tears on my cheek. Then Richie surrenders and starts bawling. Nikki goes over and puts a hand on his shoulder to comfort him. "It’s okay," Nikki tells him. "Sometimes real guys cry too."

Richie jumps up and stumbles into the kitchen. "I’ll check on the pizza," he says. When he comes back his eyes are red and he has slices for all of us. Between the beer Nikki poured on him and the flood of tears he’s been unable to dam up, he’s a wet and sorry sight. I’ll take him for a friend though, even if he doesn’t appreciate Peyton.

Saturday, July 26, 2008

Sunday, July 20, 2008

cavemen, first drafts, and the quest for fire

The other day, while watching that insurance commercial where the sophisticated caveman, upset by Geico’s slogan (“So easy a caveman can do it”), reminds modern man that he was the one who walked upright, discovered fire, and invented the wheel, I wanted the caveman to add storytelling to his list of great achievements, and was about to yell my request at the TV screen, but instead I began thinking about the caveman sitting around the fire at night with his comrades, telling the story of the day’s great hunt, and how that telling must have been like a writer’s first draft and would probably be improved upon, embellished no doubt, in later tellings around other fires. In my own caveman fantasies, of course, I am the one who invents the run-on sentence.

We all assume that the second draft will be better than the first, the third draft better than the second, and so on. Anne Lamott, in Bird by Bird, observed that even the best writers produce “shitty” first drafts, thus encouraging all those who are careful to stay upwind of their first draft to jump into a second draft, filled with courage and hope. Writing is rewriting, we are told. Who can argue with that? Ernest Hemingway said that he rewrote the ending to A Farewell to Arms 39 times because he wanted to get the words right. From shitty to sublime in 39 steps.

But what of our caveman friend? If we ride our time machine back to that Paleolithic night, which version of the hunt do we want to hear? If I’m driving the time machine, we’re going back to the first telling, on the same day as the great hunt.

I want to sit at that fire and hear our ancient friend, still hot from the adventure, tell us what happened—beginning, middle, and end—even if his words are at times confused or redundant, his prose overrun a bit by adjectives and adverbs, his ending not revised 39 times.

I’ll accept those imperfections in order to hear the excitement in the caveman’s voice as he tells the story of the new adventure, and to see the fire reflected in his eyes, eyes that have so recently seen great danger and great success. Months, years later, after our friend has retold his story many times, we can revisit him and see how he has refined the telling, tightening the plot and smoothing the prose, embellishing the details of the hunt, employing dramatic pauses to thrill his listeners, wowing them with the 39th version of the ending. Will he still have the energy, the honesty, the truth of that first telling? Maybe. Maybe not.

We ride our time machine back to the present. We pick up a first draft and reread it, then the revisions. Has the rewriting weakened the energy, the honesty, the truth of the first draft? Whatever the answer, it’s a question we need to ask. The first draft may be imperfect, is in fact guaranteed to be imperfect, but the excitement of telling a new story is usually there. We just need to bring that spark with us as we rewrite the story.

Oh yes, the spark. The spark that awaits our discovery and fires our imagination. We could call the writer’s journey The Quest for Fire. Crank up the time machine one more time. This time we journey farther back, to a place where cavemen sit huddled together for warmth and protection on a black night, possessing no fire against the chill, missing one of their own. They hear footsteps in the distance, then closer. In fear they grip their weapons more tightly.

Then they see him. Their missing comrade has returned. They see his face illuminated by the large fiery stick he carries in his right hand. He has captured fire and brought it home. Tonight there will be a great campfire to sit around and an amazing story to hear. First draft. So easy a caveman can do it.

We all assume that the second draft will be better than the first, the third draft better than the second, and so on. Anne Lamott, in Bird by Bird, observed that even the best writers produce “shitty” first drafts, thus encouraging all those who are careful to stay upwind of their first draft to jump into a second draft, filled with courage and hope. Writing is rewriting, we are told. Who can argue with that? Ernest Hemingway said that he rewrote the ending to A Farewell to Arms 39 times because he wanted to get the words right. From shitty to sublime in 39 steps.

But what of our caveman friend? If we ride our time machine back to that Paleolithic night, which version of the hunt do we want to hear? If I’m driving the time machine, we’re going back to the first telling, on the same day as the great hunt.

I want to sit at that fire and hear our ancient friend, still hot from the adventure, tell us what happened—beginning, middle, and end—even if his words are at times confused or redundant, his prose overrun a bit by adjectives and adverbs, his ending not revised 39 times.

I’ll accept those imperfections in order to hear the excitement in the caveman’s voice as he tells the story of the new adventure, and to see the fire reflected in his eyes, eyes that have so recently seen great danger and great success. Months, years later, after our friend has retold his story many times, we can revisit him and see how he has refined the telling, tightening the plot and smoothing the prose, embellishing the details of the hunt, employing dramatic pauses to thrill his listeners, wowing them with the 39th version of the ending. Will he still have the energy, the honesty, the truth of that first telling? Maybe. Maybe not.

We ride our time machine back to the present. We pick up a first draft and reread it, then the revisions. Has the rewriting weakened the energy, the honesty, the truth of the first draft? Whatever the answer, it’s a question we need to ask. The first draft may be imperfect, is in fact guaranteed to be imperfect, but the excitement of telling a new story is usually there. We just need to bring that spark with us as we rewrite the story.

Oh yes, the spark. The spark that awaits our discovery and fires our imagination. We could call the writer’s journey The Quest for Fire. Crank up the time machine one more time. This time we journey farther back, to a place where cavemen sit huddled together for warmth and protection on a black night, possessing no fire against the chill, missing one of their own. They hear footsteps in the distance, then closer. In fear they grip their weapons more tightly.

Then they see him. Their missing comrade has returned. They see his face illuminated by the large fiery stick he carries in his right hand. He has captured fire and brought it home. Tonight there will be a great campfire to sit around and an amazing story to hear. First draft. So easy a caveman can do it.

Friday, July 18, 2008

goldilocks 101: how do you know when it's just right?

This is not about the legal and moral issues attached to blondes who break and enter. Nor is it even about blondes in general. This is not the time and place to talk about one particular blonde who proposed to me in the frozen food section of a supermarket in Seattle (I said no, of course; a guy wants a little more romance at times like that).

What this is about, in fact, is one particular blonde’s unfailing instinct for rejecting inferior choices and pouncing on just the right option. It’s what made her famous, that and the fact that she walked uninvited into the home of three bears who didn’t know her from Madonna. Like Madonna, of course, she is known by one name.

Ask any child and you’ll hear the kid’s account of Goldilocks. Ask astronomers and they’ll tell you about the “Goldilocks zone,” where the temperature of a distant planet is just right for water to be liquid at its surface and thus able to support life as we know it. Ask me and I’ll tell you about what writers can learn from this famous blonde.

Writers always seem to be struggling to find their own Goldilocks zone, to know when their work is just right. Goldilocks knew, she knew, which bowl of porridge was too hot, which was too cold, and which was just right. The story doesn’t tell us how she knew, but I think it was not something she had to analyze before she chose the baby bear’s bowl of porridge and ate it all up. Her taste buds told her. She knew what she liked. Going in, she had some experience with porridge.

Then the business with the chairs. The daddy chair? Too hard. The mama chair? Too soft. It was only after sampling these two that Goldilocks chose the baby chair and declared it to be “just right.” Same sequence as with the porridge. She had to taste from all three bowls and sit on all three chairs before knowing how to proceed. Unfortunately, Goldilocks must have spent half her life in the buffet line, because the baby bear’s chair broke beneath her.

Undeterred, our daring heroine went upstairs to see what other damage she could inflict. As we well remember, Goldilocks had to try out all three beds before deciding that the baby bear’s bed was just right. It was so right that she soon fell asleep and was there when the three bears returned from their picnic and found the blonde invader sacked out. Much shouting and merriment ensued, leading to a frightening lesson for children who can’t resist porridge in strange homes. We are told that blondes no longer wander into bear homes in the Black Forest, although they do find other ways to wreak havoc. They have been spotted (blondes, not bears) as far away as supermarkets in Seattle.

All right, so Goldilocks was not a great burglar, but she does point the way for writers who want to know when it’s just right. How long should my story be? You can read Aristotle’s thoughts on this in his Poetics. I was taught in college that a work should have magnitude, “that quality of a work of art whereby it has as many parts as is consistent with a single view of parts and whole.” How many parts? How many pages? Not too many, and not too few, but just right.

One way to discover how long is “just right” is to write too few pages, then write too many. The right length lies somewhere in between. To test the value of a part, take it out. If Shakespeare removes the character Ophelia from Hamlet, is the tragedy diminished? If he gives Ophelia a part twice as large, is the tragedy improved? Shakespeare knew the answers to these questions.

We know as well the answers for our own stories. That knowledge arrives, however, only after we fiddle with the parts: adding, removing, shuffling, and finally arriving at the right length. It is difficult to question the length of the Goldilocks story. Bears leaving the house for a picnic (no need for their back story); cheeky little blonde walking in and helping herself to the food and furniture (we don’t require her criminal history, just get on with the story); the bears returning home and discovering the naughty blonde. Beginning, middle, and end.

Three bears? Perfect. Does baby bear need a big brother or sister? Maybe in real life, but not in our story. Two bowls of porridge? Something missing there. Four chairs? Too many by one. And is the bed part not perfectly placed for a dramatic climax? You bet.

Recently I was reminded of the reality of the late arriving answer. We ask questions of our stories, lumber through a first draft, shake our heads and begin a second draft, and so on until at last we find the answers and our story is just right, or as right as we can make it. Consider the case of Daniel Quinn. In 1992 Quinn published Ishmael, a remarkable little novel in which the title character, a half ton silverback gorilla, teaches the narrator about ecology, life, freedom, and the human condition.

Quinn’s first version of the award-winning novel was written 15 years earlier, in 1977, and was followed by seven more complete and distinct versions as the writer struggled with the book. The eighth, and final, version was the late arriving answer to Quinn’s question. In this published version the gorilla character, Ishmael, appears for the first time. Quinn also made another major change in this final version: he decided to write the book as a novel. And so it was, in another inspirational story for writers, that publication came as Quinn was about to admit defeat.

Perhaps there were other, long lost versions of the Goldilocks story. Goldilocks and the Three Frogs? Redlocks and the Seven Bears? Goldilocks, the Three Pigs, and the Building Inspector? We accept the classics as chiseled in stone, but we should remember the early uncertain steps in the creative process.

The faces of the four Presidents at Mount Rushmore we take for granted today, but in the early plans the faces would have been those of Lewis and Clark, or Washington alone. Four’s a good number on Rushmore. It’s just right. Consider too that the sculpture is unfinished. Borglum’s original design called for a sculpture of the Presidents to their waists, but time and money only provided for their heads. Give me just the heads every time. At Rushmore less is more. This is a lesson for writers to keep in mind. If we write four drafts of a novel, maybe that third draft is the answer.

Woody Allen wrote a comic story about the invention of the sandwich by the Earl of Sandwich, in which the earl does extensive research into cold cuts and cheeses, but fails miserably again and again with his early experiments. Then, one glorious day, the earl decides to put the meat inside two slices of bread, thus making deli history.

For some reason (and we might as well just accept it, as we accept gravity), you can’t invent the sandwich on day one. You can’t write Ishmael in one draft. And that notorious blonde with burglary in her heart? I like to believe she started out to visit her grandmother. She missed the wolf, but she did find other instructive wildlife to keep us all entertained for lo these many years.

What this is about, in fact, is one particular blonde’s unfailing instinct for rejecting inferior choices and pouncing on just the right option. It’s what made her famous, that and the fact that she walked uninvited into the home of three bears who didn’t know her from Madonna. Like Madonna, of course, she is known by one name.

Ask any child and you’ll hear the kid’s account of Goldilocks. Ask astronomers and they’ll tell you about the “Goldilocks zone,” where the temperature of a distant planet is just right for water to be liquid at its surface and thus able to support life as we know it. Ask me and I’ll tell you about what writers can learn from this famous blonde.

Writers always seem to be struggling to find their own Goldilocks zone, to know when their work is just right. Goldilocks knew, she knew, which bowl of porridge was too hot, which was too cold, and which was just right. The story doesn’t tell us how she knew, but I think it was not something she had to analyze before she chose the baby bear’s bowl of porridge and ate it all up. Her taste buds told her. She knew what she liked. Going in, she had some experience with porridge.

Then the business with the chairs. The daddy chair? Too hard. The mama chair? Too soft. It was only after sampling these two that Goldilocks chose the baby chair and declared it to be “just right.” Same sequence as with the porridge. She had to taste from all three bowls and sit on all three chairs before knowing how to proceed. Unfortunately, Goldilocks must have spent half her life in the buffet line, because the baby bear’s chair broke beneath her.

Undeterred, our daring heroine went upstairs to see what other damage she could inflict. As we well remember, Goldilocks had to try out all three beds before deciding that the baby bear’s bed was just right. It was so right that she soon fell asleep and was there when the three bears returned from their picnic and found the blonde invader sacked out. Much shouting and merriment ensued, leading to a frightening lesson for children who can’t resist porridge in strange homes. We are told that blondes no longer wander into bear homes in the Black Forest, although they do find other ways to wreak havoc. They have been spotted (blondes, not bears) as far away as supermarkets in Seattle.

All right, so Goldilocks was not a great burglar, but she does point the way for writers who want to know when it’s just right. How long should my story be? You can read Aristotle’s thoughts on this in his Poetics. I was taught in college that a work should have magnitude, “that quality of a work of art whereby it has as many parts as is consistent with a single view of parts and whole.” How many parts? How many pages? Not too many, and not too few, but just right.

One way to discover how long is “just right” is to write too few pages, then write too many. The right length lies somewhere in between. To test the value of a part, take it out. If Shakespeare removes the character Ophelia from Hamlet, is the tragedy diminished? If he gives Ophelia a part twice as large, is the tragedy improved? Shakespeare knew the answers to these questions.

We know as well the answers for our own stories. That knowledge arrives, however, only after we fiddle with the parts: adding, removing, shuffling, and finally arriving at the right length. It is difficult to question the length of the Goldilocks story. Bears leaving the house for a picnic (no need for their back story); cheeky little blonde walking in and helping herself to the food and furniture (we don’t require her criminal history, just get on with the story); the bears returning home and discovering the naughty blonde. Beginning, middle, and end.

Three bears? Perfect. Does baby bear need a big brother or sister? Maybe in real life, but not in our story. Two bowls of porridge? Something missing there. Four chairs? Too many by one. And is the bed part not perfectly placed for a dramatic climax? You bet.

Recently I was reminded of the reality of the late arriving answer. We ask questions of our stories, lumber through a first draft, shake our heads and begin a second draft, and so on until at last we find the answers and our story is just right, or as right as we can make it. Consider the case of Daniel Quinn. In 1992 Quinn published Ishmael, a remarkable little novel in which the title character, a half ton silverback gorilla, teaches the narrator about ecology, life, freedom, and the human condition.

Quinn’s first version of the award-winning novel was written 15 years earlier, in 1977, and was followed by seven more complete and distinct versions as the writer struggled with the book. The eighth, and final, version was the late arriving answer to Quinn’s question. In this published version the gorilla character, Ishmael, appears for the first time. Quinn also made another major change in this final version: he decided to write the book as a novel. And so it was, in another inspirational story for writers, that publication came as Quinn was about to admit defeat.

Perhaps there were other, long lost versions of the Goldilocks story. Goldilocks and the Three Frogs? Redlocks and the Seven Bears? Goldilocks, the Three Pigs, and the Building Inspector? We accept the classics as chiseled in stone, but we should remember the early uncertain steps in the creative process.

The faces of the four Presidents at Mount Rushmore we take for granted today, but in the early plans the faces would have been those of Lewis and Clark, or Washington alone. Four’s a good number on Rushmore. It’s just right. Consider too that the sculpture is unfinished. Borglum’s original design called for a sculpture of the Presidents to their waists, but time and money only provided for their heads. Give me just the heads every time. At Rushmore less is more. This is a lesson for writers to keep in mind. If we write four drafts of a novel, maybe that third draft is the answer.

Woody Allen wrote a comic story about the invention of the sandwich by the Earl of Sandwich, in which the earl does extensive research into cold cuts and cheeses, but fails miserably again and again with his early experiments. Then, one glorious day, the earl decides to put the meat inside two slices of bread, thus making deli history.

For some reason (and we might as well just accept it, as we accept gravity), you can’t invent the sandwich on day one. You can’t write Ishmael in one draft. And that notorious blonde with burglary in her heart? I like to believe she started out to visit her grandmother. She missed the wolf, but she did find other instructive wildlife to keep us all entertained for lo these many years.

Wednesday, July 16, 2008

heartbreak number 437

[While folks on the Mainland daydream about romantic Hawaii, I sometimes daydream about how people live on the Mainland. I mostly see them on cable TV. You know, people like Ross and Rachel. The following short short story is from The Breakup Queen, a collection of 18 contemporary Hawaii writers.]

"Heartbreak Number 437"

Ross has entered the Twilight Zone. He stares at the television screen, not believing what he is seeing and hearing. His mind and body still heavy with sleep, he is a bear just emerging from a long hibernation. His surroundings are familiar, the same apartment and furniture, the same large window, but something is missing. It’s quiet, too quiet. Where are the voices? All those voices, the voices of friends, the voices of what has now become his past, reduced to the faintest of echoes. What the hell has happened to his world?

He moves closer to the TV, studying the young woman, her familiar voice the only one remaining from the old gang. She is beautiful and sad, and all the more beautiful for her sadness. Why does the woman interviewing her keep calling her Jennifer? Her real name is Rachel. His Rachel.

“Hey, hey,” Ross says, recovering his power of speech, fairly eloquent for a bear just out of hibernation. “Hey, hey, hey.” More eloquent yet. “Hey, Rachel, it’s me,” his small bear voice pleads. He kneels in front of the TV, his face only a foot from her image, but Rachel ignores him, pretending to be Jennifer, talking about what has made her so sad.

It’s all about someone named Brad. Ross tries to follow what the two women are saying about Brad. It makes no sense. Ross believes, for a moment, that Rachel must have a twin sister named Jennifer, that it is Jennifer who has gotten mixed up with this Brad character and Brad has broken her heart. Poor Jennifer. When Rachel walks in the door, Ross will ask her why she never told him she had a twin sister, and ask if there is anything they can do to make her feel better.

Just then Jennifer looks into the camera and she and Ross are eye-to-eye. In that instant the twin sister theory evaporates and Ross is looking at Rachel. She is saying how lonely she has been. Now Ross is just as lonely as she is, which he finds strangely comforting.

Rachel begins talking about what Brad did with another woman. She says that Brad is missing a sensitivity chip. Sensitivity chip? Ross brightens. “Hey, Rachel,” he says. “It’s me, Ross.” He jumps to his feet, his arms spread now, the bear man ready for action. “You know I have a sensitivity chip,” he says. “Remember?” He has stopped listening to the interview on the screen. “Remember how sensitive I am? If I were any more sensitive I’d be gay!”

Ross walks briskly to the window. The sky has lightened. He feels the warm sun on his face. Another spring has arrived. Rachel will be home soon. She will remember him and forget all about Brad. Maybe the voices will return as well. The old friends. Ross waits by the window.

"Heartbreak Number 437"

Ross has entered the Twilight Zone. He stares at the television screen, not believing what he is seeing and hearing. His mind and body still heavy with sleep, he is a bear just emerging from a long hibernation. His surroundings are familiar, the same apartment and furniture, the same large window, but something is missing. It’s quiet, too quiet. Where are the voices? All those voices, the voices of friends, the voices of what has now become his past, reduced to the faintest of echoes. What the hell has happened to his world?

He moves closer to the TV, studying the young woman, her familiar voice the only one remaining from the old gang. She is beautiful and sad, and all the more beautiful for her sadness. Why does the woman interviewing her keep calling her Jennifer? Her real name is Rachel. His Rachel.

“Hey, hey,” Ross says, recovering his power of speech, fairly eloquent for a bear just out of hibernation. “Hey, hey, hey.” More eloquent yet. “Hey, Rachel, it’s me,” his small bear voice pleads. He kneels in front of the TV, his face only a foot from her image, but Rachel ignores him, pretending to be Jennifer, talking about what has made her so sad.

It’s all about someone named Brad. Ross tries to follow what the two women are saying about Brad. It makes no sense. Ross believes, for a moment, that Rachel must have a twin sister named Jennifer, that it is Jennifer who has gotten mixed up with this Brad character and Brad has broken her heart. Poor Jennifer. When Rachel walks in the door, Ross will ask her why she never told him she had a twin sister, and ask if there is anything they can do to make her feel better.

Just then Jennifer looks into the camera and she and Ross are eye-to-eye. In that instant the twin sister theory evaporates and Ross is looking at Rachel. She is saying how lonely she has been. Now Ross is just as lonely as she is, which he finds strangely comforting.

Rachel begins talking about what Brad did with another woman. She says that Brad is missing a sensitivity chip. Sensitivity chip? Ross brightens. “Hey, Rachel,” he says. “It’s me, Ross.” He jumps to his feet, his arms spread now, the bear man ready for action. “You know I have a sensitivity chip,” he says. “Remember?” He has stopped listening to the interview on the screen. “Remember how sensitive I am? If I were any more sensitive I’d be gay!”

Ross walks briskly to the window. The sky has lightened. He feels the warm sun on his face. Another spring has arrived. Rachel will be home soon. She will remember him and forget all about Brad. Maybe the voices will return as well. The old friends. Ross waits by the window.

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

falling in love with first person

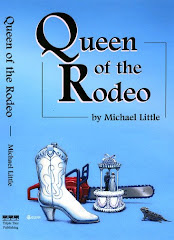

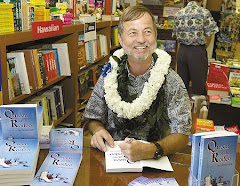

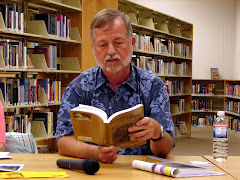

I’m trying to remember the first time I wrote in first person point of view. There’s a flickering memory of an assignment in fourth grade, writing about an imaginary trip across Texas. I remember heading west from Houston, in a car driven apparently by someone else, someone with a driver’s license. Our teacher—whose name was Bird or Boyd, both taught at Alamo Elementary, much to our delight—loved the “nice details” of the rolling countryside around Austin. Unfortunately, I had never been west of Austin, so the narrative, and the nice details, flattened out after that. I believe I was on my way to the golden land of California, only God knows why, perhaps to see the Golden Gate Bridge, or John Wayne in Hollywood, or any of the many movie cowboys whose larger-than-life images and heroic deeds filled my childhood. What I needed was to write a story about the cowboys, but that would have to wait several decades.

When I finally arrived in California after college, it was filled not with cowboys but with hippies. San Francisco is not noted for its buckaroos, even if it does have a Cow Palace. I did finally see the famous bridge, and discovered the wineries north of the city, and their tasting rooms. By then I had left the old movie cowboys, and my childhood, back in Texas. My writing had become a long series of academic exercises, mostly literary analysis and detailed critical journeys over the rolling countryside of modern American literature. At the University of Delaware, before I moved west, I had seen not a single cowboy, unless you count watching Jon Voight up on the big screen with Dustin Hoffman in Midnight Cowboy.

When I migrated up the coast to Seattle—trading in the bridge for Puget Sound ferries, and the wineries for Pike Place Market—I landed in a fiction writing class and tried my hand at a short story. No cowboys inhabited that narrative, only a young guy working in a Seattle ice cream shop. This story had an amazingly large number of nice details (perhaps I was remembering my glory days as an acclaimed writer in fourth grade). It also had a first-person narrator. I could hear his voice. Unlike the fourth-grade story, however, this ice-cream story went nowhere—not to California, not to Austin, not even down the street to Pike Place Market (now that would have been a great setting). After a few highly detailed pages, the story fizzled out for lack of plot. My narrator had no goal, no great passion (I realize now), not even a passion for ice cream. I did enjoy the first-person storytelling, and I would return to it when I moved on to Hawaii and began writing about cowboys.

Up to this point I had just been flirting with first-person point of view. She was an intriguing woman I had seen all my life. She was always in the company of someone else, other writers. With other writers, some of them famous and brilliant, she was always changing, dressed differently for each writer, her voice never the same from story to story, her moods voltaile. Should I ask her out? If I did, and she said yes, would it result in disaster? Would there be a second chance?

For a long time I just watched her, while I stayed with third-person point of view, my longtime companion, with whom I felt safe and comfortable. It’s not as if I couldn’t tell a story with good old third-person. With third-person I could still climb inside a character’s head and tell a story from his point of view. Or her point of view. I wrote an entire novel, Escape from the Dream House, inside the head of Barbie! Who knew that Barbie could have such an exciting life in the real world once she ditched Ken?

And yet I would continue catching glimpses of the mysterious first-person lady, who always seemed so exotic, her life impulsive and fascinating. One morning I set out to write a short story about the ritual of picking mangoes, an autobiographical tale told from the point of view of a man who has married into a local Japanese-American family and been invited to help harvest mangoes from the great tree in front of the family home in Kaimuki. To tell this highly personal story, one that was at the very heart of my life in Hawaii, I had two options. I could distance myself a bit with third-person point of view. Or I could dive headlong into the personal emotions of the story and make it more intimate by letting the reader hear the voice of the central character.

I don’t recall now whether I walked up to first-person and asked her out for this mango story, or whether she walked up behind me and whispered in my ear (I kind of like the version in which she whispers her invitation and I go with her). I do know, however, that we hit it off great, from the beginning. The timing was right. The story was right. I was ready for first-person, and she was ready for me. At one point she looked at me and whispered, “What took you so long?” The story, which I called “Mango Lessons,” opens with setting:

“Grampa, come down!”

The small boy’s words were soon echoed by others who stood under the large old mango tree, enjoying its shade on a hot June day in Kaimuki, not far from Waikiki and Diamond Head, and even closer to Leonard’s Bakery, which produced the sweet malasada the small boy held in one hand.

In the fifth paragraph the narrator identifies himself, and his role in the story, and we’re off and running with first-person:

And there I was, standing in the driveway, holding the long, heavy pole with the hook and basket on the end, the magic instrument entrusted to me, the newcomer, the haole man who had married the younger daughter. The tall haole man. The “tall man,” as the small boy first called me. The Japanese-American family, presided over by its mango-climbing patriarch, had admitted a white man into its ranks, a remarkable precedent.

Until this day—the day of the mango picking—I had been under the illusion that my acceptance depended on my keeping a smile on the younger daughter’s face, and I had done all in my power to produce and sustain that smile. But the illusion was quickly vanishing, as surely as the malasada that the small boy was devouring under the mango tree. Now I knew why I had been accepted. I must have appeared on the scene like the answer to the parents’ prayer. “Please send us a six-foot man who can reach the tall mangoes.” They had neglected to ask for a six-foot Japanese man, and now they were stuck with me.

And so it began, my affair with the exotic woman who often walked up behind me and whispered in my ear. The more stories I wrote in first-person point of view—whether they were about Texas cowboys, or Reno rodeo queens, or folks in Hawaii—the more natural it felt. Sometimes I would seek her out. Sometimes we would just set out together, no invitation needed. She became a familiar companion, but never dull, never predictable. Her moods were wild as ever, her voice as unpredictable as life itself.

When I finally arrived in California after college, it was filled not with cowboys but with hippies. San Francisco is not noted for its buckaroos, even if it does have a Cow Palace. I did finally see the famous bridge, and discovered the wineries north of the city, and their tasting rooms. By then I had left the old movie cowboys, and my childhood, back in Texas. My writing had become a long series of academic exercises, mostly literary analysis and detailed critical journeys over the rolling countryside of modern American literature. At the University of Delaware, before I moved west, I had seen not a single cowboy, unless you count watching Jon Voight up on the big screen with Dustin Hoffman in Midnight Cowboy.

When I migrated up the coast to Seattle—trading in the bridge for Puget Sound ferries, and the wineries for Pike Place Market—I landed in a fiction writing class and tried my hand at a short story. No cowboys inhabited that narrative, only a young guy working in a Seattle ice cream shop. This story had an amazingly large number of nice details (perhaps I was remembering my glory days as an acclaimed writer in fourth grade). It also had a first-person narrator. I could hear his voice. Unlike the fourth-grade story, however, this ice-cream story went nowhere—not to California, not to Austin, not even down the street to Pike Place Market (now that would have been a great setting). After a few highly detailed pages, the story fizzled out for lack of plot. My narrator had no goal, no great passion (I realize now), not even a passion for ice cream. I did enjoy the first-person storytelling, and I would return to it when I moved on to Hawaii and began writing about cowboys.

Up to this point I had just been flirting with first-person point of view. She was an intriguing woman I had seen all my life. She was always in the company of someone else, other writers. With other writers, some of them famous and brilliant, she was always changing, dressed differently for each writer, her voice never the same from story to story, her moods voltaile. Should I ask her out? If I did, and she said yes, would it result in disaster? Would there be a second chance?

For a long time I just watched her, while I stayed with third-person point of view, my longtime companion, with whom I felt safe and comfortable. It’s not as if I couldn’t tell a story with good old third-person. With third-person I could still climb inside a character’s head and tell a story from his point of view. Or her point of view. I wrote an entire novel, Escape from the Dream House, inside the head of Barbie! Who knew that Barbie could have such an exciting life in the real world once she ditched Ken?

And yet I would continue catching glimpses of the mysterious first-person lady, who always seemed so exotic, her life impulsive and fascinating. One morning I set out to write a short story about the ritual of picking mangoes, an autobiographical tale told from the point of view of a man who has married into a local Japanese-American family and been invited to help harvest mangoes from the great tree in front of the family home in Kaimuki. To tell this highly personal story, one that was at the very heart of my life in Hawaii, I had two options. I could distance myself a bit with third-person point of view. Or I could dive headlong into the personal emotions of the story and make it more intimate by letting the reader hear the voice of the central character.

I don’t recall now whether I walked up to first-person and asked her out for this mango story, or whether she walked up behind me and whispered in my ear (I kind of like the version in which she whispers her invitation and I go with her). I do know, however, that we hit it off great, from the beginning. The timing was right. The story was right. I was ready for first-person, and she was ready for me. At one point she looked at me and whispered, “What took you so long?” The story, which I called “Mango Lessons,” opens with setting:

“Grampa, come down!”

The small boy’s words were soon echoed by others who stood under the large old mango tree, enjoying its shade on a hot June day in Kaimuki, not far from Waikiki and Diamond Head, and even closer to Leonard’s Bakery, which produced the sweet malasada the small boy held in one hand.

In the fifth paragraph the narrator identifies himself, and his role in the story, and we’re off and running with first-person:

And there I was, standing in the driveway, holding the long, heavy pole with the hook and basket on the end, the magic instrument entrusted to me, the newcomer, the haole man who had married the younger daughter. The tall haole man. The “tall man,” as the small boy first called me. The Japanese-American family, presided over by its mango-climbing patriarch, had admitted a white man into its ranks, a remarkable precedent.

Until this day—the day of the mango picking—I had been under the illusion that my acceptance depended on my keeping a smile on the younger daughter’s face, and I had done all in my power to produce and sustain that smile. But the illusion was quickly vanishing, as surely as the malasada that the small boy was devouring under the mango tree. Now I knew why I had been accepted. I must have appeared on the scene like the answer to the parents’ prayer. “Please send us a six-foot man who can reach the tall mangoes.” They had neglected to ask for a six-foot Japanese man, and now they were stuck with me.

And so it began, my affair with the exotic woman who often walked up behind me and whispered in my ear. The more stories I wrote in first-person point of view—whether they were about Texas cowboys, or Reno rodeo queens, or folks in Hawaii—the more natural it felt. Sometimes I would seek her out. Sometimes we would just set out together, no invitation needed. She became a familiar companion, but never dull, never predictable. Her moods were wild as ever, her voice as unpredictable as life itself.

Monday, July 14, 2008

tough cowboys and strong women

Boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy finds girl. Ah yes, the old Hollywood formula. But what if it’s 1948, and you have Howard Hawks to produce and direct the movie, and John Wayne and Montgomery Clift and Joanne Dru to light up the big screen, and Borden Chase and Charles Schnee to write a powerful screenplay, and ... since the story is about the first great cattle drive on the Chisholm Trail, let’s get a few thousand head of cattle to stir up the dust and challenge the cowboys, who aren’t boys at all but men, real men, tough men.

And let’s make the women strong and brave, and ready to face the hard life of the Wild West and the hard heads of the cowboys they love. Then let’s call it Red River, and make a classic that will take its place with Stagecoach and High Noon and Shane and Lonesome Dove and the very best examples of that great American invention, the Western.

And what if you play with the old formula, so that the film begins with boy loses girl? Tom Dunson (John Wayne) leaves a wagon train in 1851 to head south to the Red River and Texas to raise cattle, but he leaves behind his sweetheart, Fen (Coleen Gray), promising to send for her later. It’s an emotional, moving opening scene, and the words that Dunson and the young woman speak establish that we’re watching tough cowboys and the strong women they underestimate:

Fen: Please take me with you. I’m strong. I can stand anything you can.

Tom: It’s too much for a woman.

Fen: Too much for a woman? Put your arms around me, Tom. (They hug and kiss each other.) Hold me. Feel me in your arms. Do I feel weak, Tom? I don’t, do I? Oh, you’ll need me. You’ll need a woman. You need what a woman can give you to do what you have to do. Oh listen to me, Tom. Listen with your head and your heart too. The sun only shines half the time, Tom. The other half is night.

Tom: I’ve made up my mind.

Fen: Oh change your mind, Tom. Just once in your life change your mind.

Tom: I’ll send for ya. Will ya come?

Fen: Of course I’ll come. But you’re wrong.

And he is wrong. Believing that "It’s too much for a woman," Tom Dunson loses his love. After Dunson leaves, Commanches attack the wagon train and Fen is killed. So boy loses girl, forever. To fill the void, Dunson devotes his life to raising cattle in Texas. The film jumps 15 years ahead, to a time when he has a great herd but there’s no cash market for them in post-Civil War Texas. His only hope is to drive the cattle a thousand miles north, to the railroad in Missouri.

So begins the great cattle drive, as Dunson tells his adopted son, Matt (Montgomery Clift in his first film), to "take ‘em to Missouri" and we have the famous early morning "yee-hah" scene, with all the cowboys waving their hats in the air and yelling to cue the cattle and begin the great adventure. In the long middle scenes of Red River, it’s all about brave cowboys and lots of beef on the hoof and stampedes and hardship, and it’s extremely romantic in its way.

And yet the romance of the heart needs a woman, so eventually Tess Millay (Joanne Dru in her second film) arrives in the film as part of a wagon train on its way from New Orleans to Nevada to set up a gambling establishment. When this band of gamblers and prostitutes is attacked by Indians, Matt and three other men ride up to help the people in the circled wagons.

Matt, naturally, finds himself next to Tess Millay, a pretty young woman who is not a prostitute, although he doesn’t know that. Tess is fighting alongside the men, firing at the attacking Indians, as the protective cowboy tells her to stay down. She tells Matt, "What are you so mad about? I asked you why you’re angry. Is it because - because some of your men might get hurt, killed maybe?" In mid-sentence she is struck in the shoulder by an arrow. She keeps talking and faints in his arms, but not before slapping his face for the attitude he shows toward her.

The wagon train manages to fight off the Indians and Matt returns to Tess to remove the arrow from her shoulder and suck out the poison—an amazingly intimate, almost erotic, kind of first date for these two. She keeps up her interrogation, asking him if he’s angry about helping a bunch of women, and of course she’s angry because he assumes that she’s one of the prositutes. But there’s no mistaking the immediate physical attraction between Matt and Tess. So boy meets girl, even if it’s not the boy who lost another girl at the beginning of the film, and Tess may be even stronger than Tom Dunson’s sweetheart, Fen.

The dialogue between these two crackles as they discuss Tom Dunson. (Matt and the cowboys have taken the herd from the tyrannical Dunson, in the Mutiny on the Bounty Meets the Chisholm Trail part of the film.)

Tess: Why does he think that way?

Matt: Because he got to a place where, see, he’d taken empty land used for nothin’, made it the biggest ranch in the state of Texas. Fought to keep it...one bull and one cow, that’s all he started with...After he’d done all that, gotten what he’d been after for so long, it wasn’t worth anything...So he started this drive. Everybody said, ‘you can’t make it. You’ll never get there.’ He was the only one believed we could. He had to believe it. So he started thinking one way, his way. He told men what to do and made ‘em do it. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have got as far as we did. He started ‘em for Missouri and all he knew was he had to get there. I took his herd away from him.

Tess: You love him, don’t you? He must love you. That wouldn’t be hard. (She kisses Matt on the lips.) Did you like that?

Matt: I’ve always been kind of slow in making up my mind.

Tess: Maybe I can help. (They kiss again.)

Matt: I don’t need any more help but will you do that again? (They kiss again.)

Once she enters the film, Tess Millay is the equal of any of the men. She has another sensual moment with Matt where she runs her fingers lightly over his face and his lips as they talk, and you can just imagine the butter melting again in all the boxes of popcorn in the theatre.

Tess has a scene later with Tom Dunson. She will do anything to keep Dunson from killing the mutinous Matt, whether it means marrying Dunson or shooting him (she has a gun hidden in her arm sling) or simply begging. At the end of the film, when the cowboys and cattle have reached the end of the drive and it’s time to celebrate, naturally Matt waits for Dunson to ride into town, and because it’s John Wayne you know there’s going to be a fist fight, and a good one. But even during the fight Tess Millay has her role to play, scolding the two men and shaming them.

Tess: Stop it. Stop it. Stop makin’ a holy...Stop it I said. I’m mad, good and mad. And who wouldn’t be. (To Dunson) You Dunson, pretendin’ you’re gonna kill him. Why, it’s the last thing in the world you...(Dunson moves.) Stay still. I’m mad I told ya. (To Matt) And you Matthew Garth, gettin’ your face all beat up and all bloody. You oughta see how, you oughta see how silly you look, like, like somethin’ the cat dragged - STAY STILL - What a fool I’ve been, expectin’ trouble for days when, when anybody with half a mind would know you two love each other. (To Dunson) It took somebody else to shoot ya. He wouldn’t do it. Are ya hurt?

Dunson: No, just nicked the...

Tess: Then stay still. No, don’t stay still. I changed my mind. Go ahead. Beat each other crazy. Maybe it will put the sense in both of ya. Go ahead. Go on. Do it! (After angrily thrusting her gun into the stomach of a cowhand/bystander, she marches off, disgusted by both of them.)

The next line belongs to Tom Dunson, and it’s a winner: "You’d better marry that girl, Matt." To which Matt replies, "Yeah, I think I...Hey, when are you gonna stop telling people what to do?" Cue the music, cue the cattle, cue the credits, cue the reviewers, and cue the generations of movie fans who have come to love all 125 minutes of this classic, with its beautiful black and white cinematography, its young Montgomery Clift, its feisty Joanne Dru, and an often underrated actor, the Duke, in one of his finest roles.

And let’s make the women strong and brave, and ready to face the hard life of the Wild West and the hard heads of the cowboys they love. Then let’s call it Red River, and make a classic that will take its place with Stagecoach and High Noon and Shane and Lonesome Dove and the very best examples of that great American invention, the Western.

And what if you play with the old formula, so that the film begins with boy loses girl? Tom Dunson (John Wayne) leaves a wagon train in 1851 to head south to the Red River and Texas to raise cattle, but he leaves behind his sweetheart, Fen (Coleen Gray), promising to send for her later. It’s an emotional, moving opening scene, and the words that Dunson and the young woman speak establish that we’re watching tough cowboys and the strong women they underestimate:

Fen: Please take me with you. I’m strong. I can stand anything you can.

Tom: It’s too much for a woman.

Fen: Too much for a woman? Put your arms around me, Tom. (They hug and kiss each other.) Hold me. Feel me in your arms. Do I feel weak, Tom? I don’t, do I? Oh, you’ll need me. You’ll need a woman. You need what a woman can give you to do what you have to do. Oh listen to me, Tom. Listen with your head and your heart too. The sun only shines half the time, Tom. The other half is night.

Tom: I’ve made up my mind.

Fen: Oh change your mind, Tom. Just once in your life change your mind.

Tom: I’ll send for ya. Will ya come?

Fen: Of course I’ll come. But you’re wrong.

And he is wrong. Believing that "It’s too much for a woman," Tom Dunson loses his love. After Dunson leaves, Commanches attack the wagon train and Fen is killed. So boy loses girl, forever. To fill the void, Dunson devotes his life to raising cattle in Texas. The film jumps 15 years ahead, to a time when he has a great herd but there’s no cash market for them in post-Civil War Texas. His only hope is to drive the cattle a thousand miles north, to the railroad in Missouri.

So begins the great cattle drive, as Dunson tells his adopted son, Matt (Montgomery Clift in his first film), to "take ‘em to Missouri" and we have the famous early morning "yee-hah" scene, with all the cowboys waving their hats in the air and yelling to cue the cattle and begin the great adventure. In the long middle scenes of Red River, it’s all about brave cowboys and lots of beef on the hoof and stampedes and hardship, and it’s extremely romantic in its way.

And yet the romance of the heart needs a woman, so eventually Tess Millay (Joanne Dru in her second film) arrives in the film as part of a wagon train on its way from New Orleans to Nevada to set up a gambling establishment. When this band of gamblers and prostitutes is attacked by Indians, Matt and three other men ride up to help the people in the circled wagons.

Matt, naturally, finds himself next to Tess Millay, a pretty young woman who is not a prostitute, although he doesn’t know that. Tess is fighting alongside the men, firing at the attacking Indians, as the protective cowboy tells her to stay down. She tells Matt, "What are you so mad about? I asked you why you’re angry. Is it because - because some of your men might get hurt, killed maybe?" In mid-sentence she is struck in the shoulder by an arrow. She keeps talking and faints in his arms, but not before slapping his face for the attitude he shows toward her.

The wagon train manages to fight off the Indians and Matt returns to Tess to remove the arrow from her shoulder and suck out the poison—an amazingly intimate, almost erotic, kind of first date for these two. She keeps up her interrogation, asking him if he’s angry about helping a bunch of women, and of course she’s angry because he assumes that she’s one of the prositutes. But there’s no mistaking the immediate physical attraction between Matt and Tess. So boy meets girl, even if it’s not the boy who lost another girl at the beginning of the film, and Tess may be even stronger than Tom Dunson’s sweetheart, Fen.

The dialogue between these two crackles as they discuss Tom Dunson. (Matt and the cowboys have taken the herd from the tyrannical Dunson, in the Mutiny on the Bounty Meets the Chisholm Trail part of the film.)

Tess: Why does he think that way?

Matt: Because he got to a place where, see, he’d taken empty land used for nothin’, made it the biggest ranch in the state of Texas. Fought to keep it...one bull and one cow, that’s all he started with...After he’d done all that, gotten what he’d been after for so long, it wasn’t worth anything...So he started this drive. Everybody said, ‘you can’t make it. You’ll never get there.’ He was the only one believed we could. He had to believe it. So he started thinking one way, his way. He told men what to do and made ‘em do it. Otherwise, we wouldn’t have got as far as we did. He started ‘em for Missouri and all he knew was he had to get there. I took his herd away from him.

Tess: You love him, don’t you? He must love you. That wouldn’t be hard. (She kisses Matt on the lips.) Did you like that?

Matt: I’ve always been kind of slow in making up my mind.

Tess: Maybe I can help. (They kiss again.)

Matt: I don’t need any more help but will you do that again? (They kiss again.)

Once she enters the film, Tess Millay is the equal of any of the men. She has another sensual moment with Matt where she runs her fingers lightly over his face and his lips as they talk, and you can just imagine the butter melting again in all the boxes of popcorn in the theatre.

Tess has a scene later with Tom Dunson. She will do anything to keep Dunson from killing the mutinous Matt, whether it means marrying Dunson or shooting him (she has a gun hidden in her arm sling) or simply begging. At the end of the film, when the cowboys and cattle have reached the end of the drive and it’s time to celebrate, naturally Matt waits for Dunson to ride into town, and because it’s John Wayne you know there’s going to be a fist fight, and a good one. But even during the fight Tess Millay has her role to play, scolding the two men and shaming them.

Tess: Stop it. Stop it. Stop makin’ a holy...Stop it I said. I’m mad, good and mad. And who wouldn’t be. (To Dunson) You Dunson, pretendin’ you’re gonna kill him. Why, it’s the last thing in the world you...(Dunson moves.) Stay still. I’m mad I told ya. (To Matt) And you Matthew Garth, gettin’ your face all beat up and all bloody. You oughta see how, you oughta see how silly you look, like, like somethin’ the cat dragged - STAY STILL - What a fool I’ve been, expectin’ trouble for days when, when anybody with half a mind would know you two love each other. (To Dunson) It took somebody else to shoot ya. He wouldn’t do it. Are ya hurt?

Dunson: No, just nicked the...

Tess: Then stay still. No, don’t stay still. I changed my mind. Go ahead. Beat each other crazy. Maybe it will put the sense in both of ya. Go ahead. Go on. Do it! (After angrily thrusting her gun into the stomach of a cowhand/bystander, she marches off, disgusted by both of them.)

The next line belongs to Tom Dunson, and it’s a winner: "You’d better marry that girl, Matt." To which Matt replies, "Yeah, I think I...Hey, when are you gonna stop telling people what to do?" Cue the music, cue the cattle, cue the credits, cue the reviewers, and cue the generations of movie fans who have come to love all 125 minutes of this classic, with its beautiful black and white cinematography, its young Montgomery Clift, its feisty Joanne Dru, and an often underrated actor, the Duke, in one of his finest roles.

feeding the spirit

I’ve been doing a lot of thinking lately about the importance of feeding the spirit. It’s easy to go through the days of our lives caught up in the need to feed the body and its many cravings, whether we are the bold and the beautiful, or just the young and the restless, because as the world turns life has to be more than a soap opera, right? Don’t we yearn for more than dark shadows, somewhere away from the edge of night, seeking another world, a world that’s not filled with desperate housewives?!

What feeds your spirit? Yes, you, and please stop watching General Hospital for a moment. Just record it and watch it later. Or, better yet, let me give you the recap:

"Matt arrives at the free clinic to find Lucky and Harper talking to Nikolas and Nadine about Logan’s murder. Matt’s shocked and tells the cops he saw Logan and Maxie arguing at the docks. He neglects to mention that Logan was his counterfeit-drug supplier. Later, Matt tells a mysterious someone that Logan is dead and they need to move to Plan B. At the PCPD, Lucky tells Nikolas and Nadine that Jason is a suspect, but he thinks Logan was killed by a member of the Zacchara family. Nikolas doesn’t want Nadine caught up in this, but Nadine refuses to let someone get away with murder and cooperates with Lucky."

So there you have it. I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to be anywhere near that hospital, or those people. I think Matt’s right, we need to move to Plan B. Now I’m not attacking the soaps, and I know a lot of folks are watching the Korean soaps these days, and if you’ve never turned the sound off and made your own dialogue (with or without your friends in front of the tube), you just have to try it. I believe it’s a useful exercise for fiction writers.

Here’s my Plan B. I seriously doubt that it’s the same as Matt’s. I’ll leave Matt to his issues because we need to feed our spirits. Lest they starve.

The excellent news, of course, is that there are so many ways to nourish the spirit. It’s a buffet, the rich and seemingly endless kind that you can never experience totally. You can only take some of this and some of that. Or, if you’re the kind that likes to specialize, take a whole lot of one thing. Some devote their lives to exploring the beauty of the natural world. For others it’s music, or poetry, or art, or books, or theatre, or film. Many of us select “all of the above,” which was always my favorite answer to multiple choice questions in school (my least favorite was “none of the above,” which seemed like a dirty trick, one that should have been outlawed).

I’m one of those who like to taste many of the offerings from the buffet. With film, and theatre, you can enjoy several dishes at once. Give me a good story with good music and I’m hooked. Or listen to your favorite music while you read or write. If there’s a mango tree outside your window at the same time, you’re lucky (for me it’s the neighbor’s Chinese grapefruit tree—I watch the heavy fruit hanging there and wonder if someone will pick it before it falls, and how it sounds when it falls).

Feed the spirit. We’ve only touched on the many wonders of the buffet. You probably have your own list of favorite ways to nourish the spirit. I haven’t even mentioned two of the great dishes that await us as we go down the line. You see them from a distance at a buffet table. The carving station, which has its own attendant waiting to serve you ... and beyond that ... the dessert table, so important it has its own area. Watch the eyes of those who survey the dessert table. These folks are serious.

So what corresponds to the carving station and the dessert table? I hope that somewhere on your list is that small word that makes the world go round. Love. Is there anything that nourishes our spirits so well as love? Giving and receiving. Loving and being loved. The world is brighter. Your spirit soars. All kinds of love, not just romantic love. But ah, romantic love. Cue the orchestra. Cue the chocolates. Release the endorphins! Release the romance writers! And maybe we can give Rhett and Scarlett some privacy for a while, as we enjoy the innocent and hopeful world of romantic comedy.

The other great dish that feeds the spirit is faith. What are we without faith? Without hope? The spirit yearns. It travels through this life on a journey that wanders along many paths, in search of a spiritual home, or perhaps it only yearns to return to its home. During this journey the spirit is fed by faith, by hope, by love. And by prayer, spoken or unspoken.

At this point we are a long way from the world of Lucky and Harper and Nikolas and Nadine and Matt’s Plan B and the late great Logan. But if you’re anxious to get back to General Hospital, and you’re worried that you missed some critical events, I have some disturbing news for you. I won’t sugarcoat it. Here it is:

"Maxie visits Spinelli, who tells her that Jason’s been arrested and he’s investigating the case. Maxie freaks out and “accidentally” spills soda all over Spinelli’s computer. Spinelli is suspicious when Maxie firmly declares that Jason didn’t murder Logan. In events totally unrelated to Logan’s death, the Scorpios and the Drakes have brunch."

How devastating, the tragic fate of Spinelli’s computer. And yet, in the midst of all this gloom, there remains a glimmer of hope. There’s always brunch! I know you will join me in wishing the Scorpios and the Drakes a truly bountiful and nourishing buffet.

What feeds your spirit? Yes, you, and please stop watching General Hospital for a moment. Just record it and watch it later. Or, better yet, let me give you the recap:

"Matt arrives at the free clinic to find Lucky and Harper talking to Nikolas and Nadine about Logan’s murder. Matt’s shocked and tells the cops he saw Logan and Maxie arguing at the docks. He neglects to mention that Logan was his counterfeit-drug supplier. Later, Matt tells a mysterious someone that Logan is dead and they need to move to Plan B. At the PCPD, Lucky tells Nikolas and Nadine that Jason is a suspect, but he thinks Logan was killed by a member of the Zacchara family. Nikolas doesn’t want Nadine caught up in this, but Nadine refuses to let someone get away with murder and cooperates with Lucky."

So there you have it. I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to be anywhere near that hospital, or those people. I think Matt’s right, we need to move to Plan B. Now I’m not attacking the soaps, and I know a lot of folks are watching the Korean soaps these days, and if you’ve never turned the sound off and made your own dialogue (with or without your friends in front of the tube), you just have to try it. I believe it’s a useful exercise for fiction writers.

Here’s my Plan B. I seriously doubt that it’s the same as Matt’s. I’ll leave Matt to his issues because we need to feed our spirits. Lest they starve.

The excellent news, of course, is that there are so many ways to nourish the spirit. It’s a buffet, the rich and seemingly endless kind that you can never experience totally. You can only take some of this and some of that. Or, if you’re the kind that likes to specialize, take a whole lot of one thing. Some devote their lives to exploring the beauty of the natural world. For others it’s music, or poetry, or art, or books, or theatre, or film. Many of us select “all of the above,” which was always my favorite answer to multiple choice questions in school (my least favorite was “none of the above,” which seemed like a dirty trick, one that should have been outlawed).

I’m one of those who like to taste many of the offerings from the buffet. With film, and theatre, you can enjoy several dishes at once. Give me a good story with good music and I’m hooked. Or listen to your favorite music while you read or write. If there’s a mango tree outside your window at the same time, you’re lucky (for me it’s the neighbor’s Chinese grapefruit tree—I watch the heavy fruit hanging there and wonder if someone will pick it before it falls, and how it sounds when it falls).

Feed the spirit. We’ve only touched on the many wonders of the buffet. You probably have your own list of favorite ways to nourish the spirit. I haven’t even mentioned two of the great dishes that await us as we go down the line. You see them from a distance at a buffet table. The carving station, which has its own attendant waiting to serve you ... and beyond that ... the dessert table, so important it has its own area. Watch the eyes of those who survey the dessert table. These folks are serious.

So what corresponds to the carving station and the dessert table? I hope that somewhere on your list is that small word that makes the world go round. Love. Is there anything that nourishes our spirits so well as love? Giving and receiving. Loving and being loved. The world is brighter. Your spirit soars. All kinds of love, not just romantic love. But ah, romantic love. Cue the orchestra. Cue the chocolates. Release the endorphins! Release the romance writers! And maybe we can give Rhett and Scarlett some privacy for a while, as we enjoy the innocent and hopeful world of romantic comedy.

The other great dish that feeds the spirit is faith. What are we without faith? Without hope? The spirit yearns. It travels through this life on a journey that wanders along many paths, in search of a spiritual home, or perhaps it only yearns to return to its home. During this journey the spirit is fed by faith, by hope, by love. And by prayer, spoken or unspoken.

At this point we are a long way from the world of Lucky and Harper and Nikolas and Nadine and Matt’s Plan B and the late great Logan. But if you’re anxious to get back to General Hospital, and you’re worried that you missed some critical events, I have some disturbing news for you. I won’t sugarcoat it. Here it is:

"Maxie visits Spinelli, who tells her that Jason’s been arrested and he’s investigating the case. Maxie freaks out and “accidentally” spills soda all over Spinelli’s computer. Spinelli is suspicious when Maxie firmly declares that Jason didn’t murder Logan. In events totally unrelated to Logan’s death, the Scorpios and the Drakes have brunch."

How devastating, the tragic fate of Spinelli’s computer. And yet, in the midst of all this gloom, there remains a glimmer of hope. There’s always brunch! I know you will join me in wishing the Scorpios and the Drakes a truly bountiful and nourishing buffet.

our chief weapon is surprise

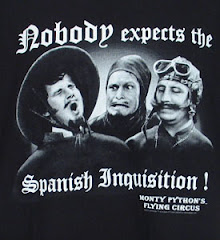

"NOBODY expects the Spanish Inquisition! Our chief weapon is surprise...surprise and fear...fear and surprise.... Our two weapons are fear and surprise...and ruthless efficiency.... Our three weapons are fear, surprise, and ruthless efficiency...and an almost fanatical devotion to the Pope.... Our four...no... Amongst our weapons.... Amongst our weaponry...are such elements as fear, surprise.... I'll come in again."

Thank you, Monty Python, for the title for this blog. NOBODY expects a blog from me, but writers write, and I write best when I'm inspired. What inspires me? My chief inspiration is Monty Python...Monty Python and Groucho Marx...Groucho Marx and Monty Python... My two inspirations are Groucho Marx and Monty Python... and Uma Thurman.... My three inspirations are Monty Python, Groucho Marx, and Uma Thurman...and an almost fanatical devotion to Mel Brooks.... My four...no... Amongst my inspirations.... Amongst my plethora of inspirations...are such elements as Groucho Marx, Monty Python.... I'll come in again.

Thank you, Monty Python, for the title for this blog. NOBODY expects a blog from me, but writers write, and I write best when I'm inspired. What inspires me? My chief inspiration is Monty Python...Monty Python and Groucho Marx...Groucho Marx and Monty Python... My two inspirations are Groucho Marx and Monty Python... and Uma Thurman.... My three inspirations are Monty Python, Groucho Marx, and Uma Thurman...and an almost fanatical devotion to Mel Brooks.... My four...no... Amongst my inspirations.... Amongst my plethora of inspirations...are such elements as Groucho Marx, Monty Python.... I'll come in again.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)