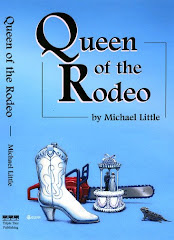

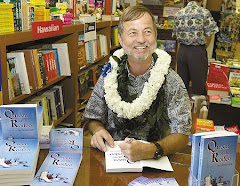

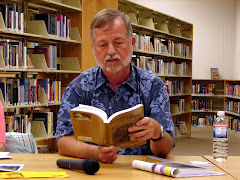

I’m trying to remember the first time I wrote in first person point of view. There’s a flickering memory of an assignment in fourth grade, writing about an imaginary trip across Texas. I remember heading west from Houston, in a car driven apparently by someone else, someone with a driver’s license. Our teacher—whose name was Bird or Boyd, both taught at Alamo Elementary, much to our delight—loved the “nice details” of the rolling countryside around Austin. Unfortunately, I had never been west of Austin, so the narrative, and the nice details, flattened out after that. I believe I was on my way to the golden land of California, only God knows why, perhaps to see the Golden Gate Bridge, or John Wayne in Hollywood, or any of the many movie cowboys whose larger-than-life images and heroic deeds filled my childhood. What I needed was to write a story about the cowboys, but that would have to wait several decades.

When I finally arrived in California after college, it was filled not with cowboys but with hippies. San Francisco is not noted for its buckaroos, even if it does have a Cow Palace. I did finally see the famous bridge, and discovered the wineries north of the city, and their tasting rooms. By then I had left the old movie cowboys, and my childhood, back in Texas. My writing had become a long series of academic exercises, mostly literary analysis and detailed critical journeys over the rolling countryside of modern American literature. At the University of Delaware, before I moved west, I had seen not a single cowboy, unless you count watching Jon Voight up on the big screen with Dustin Hoffman in Midnight Cowboy.

When I migrated up the coast to Seattle—trading in the bridge for Puget Sound ferries, and the wineries for Pike Place Market—I landed in a fiction writing class and tried my hand at a short story. No cowboys inhabited that narrative, only a young guy working in a Seattle ice cream shop. This story had an amazingly large number of nice details (perhaps I was remembering my glory days as an acclaimed writer in fourth grade). It also had a first-person narrator. I could hear his voice. Unlike the fourth-grade story, however, this ice-cream story went nowhere—not to California, not to Austin, not even down the street to Pike Place Market (now that would have been a great setting). After a few highly detailed pages, the story fizzled out for lack of plot. My narrator had no goal, no great passion (I realize now), not even a passion for ice cream. I did enjoy the first-person storytelling, and I would return to it when I moved on to Hawaii and began writing about cowboys.

Up to this point I had just been flirting with first-person point of view. She was an intriguing woman I had seen all my life. She was always in the company of someone else, other writers. With other writers, some of them famous and brilliant, she was always changing, dressed differently for each writer, her voice never the same from story to story, her moods voltaile. Should I ask her out? If I did, and she said yes, would it result in disaster? Would there be a second chance?

For a long time I just watched her, while I stayed with third-person point of view, my longtime companion, with whom I felt safe and comfortable. It’s not as if I couldn’t tell a story with good old third-person. With third-person I could still climb inside a character’s head and tell a story from his point of view. Or her point of view. I wrote an entire novel, Escape from the Dream House, inside the head of Barbie! Who knew that Barbie could have such an exciting life in the real world once she ditched Ken?

And yet I would continue catching glimpses of the mysterious first-person lady, who always seemed so exotic, her life impulsive and fascinating. One morning I set out to write a short story about the ritual of picking mangoes, an autobiographical tale told from the point of view of a man who has married into a local Japanese-American family and been invited to help harvest mangoes from the great tree in front of the family home in Kaimuki. To tell this highly personal story, one that was at the very heart of my life in Hawaii, I had two options. I could distance myself a bit with third-person point of view. Or I could dive headlong into the personal emotions of the story and make it more intimate by letting the reader hear the voice of the central character.

I don’t recall now whether I walked up to first-person and asked her out for this mango story, or whether she walked up behind me and whispered in my ear (I kind of like the version in which she whispers her invitation and I go with her). I do know, however, that we hit it off great, from the beginning. The timing was right. The story was right. I was ready for first-person, and she was ready for me. At one point she looked at me and whispered, “What took you so long?” The story, which I called “Mango Lessons,” opens with setting:

“Grampa, come down!”

The small boy’s words were soon echoed by others who stood under the large old mango tree, enjoying its shade on a hot June day in Kaimuki, not far from Waikiki and Diamond Head, and even closer to Leonard’s Bakery, which produced the sweet malasada the small boy held in one hand.

In the fifth paragraph the narrator identifies himself, and his role in the story, and we’re off and running with first-person:

And there I was, standing in the driveway, holding the long, heavy pole with the hook and basket on the end, the magic instrument entrusted to me, the newcomer, the haole man who had married the younger daughter. The tall haole man. The “tall man,” as the small boy first called me. The Japanese-American family, presided over by its mango-climbing patriarch, had admitted a white man into its ranks, a remarkable precedent.

Until this day—the day of the mango picking—I had been under the illusion that my acceptance depended on my keeping a smile on the younger daughter’s face, and I had done all in my power to produce and sustain that smile. But the illusion was quickly vanishing, as surely as the malasada that the small boy was devouring under the mango tree. Now I knew why I had been accepted. I must have appeared on the scene like the answer to the parents’ prayer. “Please send us a six-foot man who can reach the tall mangoes.” They had neglected to ask for a six-foot Japanese man, and now they were stuck with me.

And so it began, my affair with the exotic woman who often walked up behind me and whispered in my ear. The more stories I wrote in first-person point of view—whether they were about Texas cowboys, or Reno rodeo queens, or folks in Hawaii—the more natural it felt. Sometimes I would seek her out. Sometimes we would just set out together, no invitation needed. She became a familiar companion, but never dull, never predictable. Her moods were wild as ever, her voice as unpredictable as life itself.

Tuesday, July 15, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

3 comments:

Hey, Michael! Great to see you in the blogosphere! I clicked on some of your links. You have an extra "http://" in them so they don't work. :( Should be an easy to fix!

An easy fix, I meant to say.

First person should definitely be in every writer's toolbox. I don't know how it's gotten so slighted over the years.

Just as a complete non sequiter (sp?), I walked by Leonard's bakery for the first time the other day. The smell was heaven sent! And yup, that was a double entendre.

Post a Comment